An enduring preoccupation of scholars and admirers of Thomas Paine is morbidly fascinating: where in the world are Paine’s remains? The story is captivating, a tale of grave-digging, hoarding, and misinformation, but it’s also a tale with implications for the historical commemoration of intellectual and political figures. Paine’s writings are accessible to anyone who wants to read them today, but several of his most controversial works were suppressed at his death in 1809, and his legacy hotly contested. Posthumously, Paine partisans wanted the ultimate in remembrance: possession of his bones and brain.

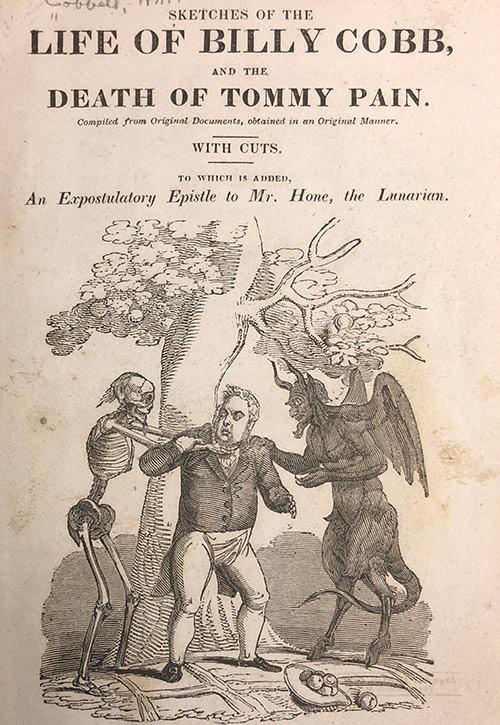

The relationship between mortal remains and historical commemoration came to mind as I leafed through English journalist William Cobbett’s 1820 picaresque illustrated poem, written to appeal to British and American working-class audiences, Sketches of the Life of Billy Cobb, and the Death of Thomas Paine.1

In the poem Cobbett described his infamous return to the United States between 1817-1819, where he dug up Paine’s remains in New Rochelle and returned them to England. A harsh critic of Paine in the 1790s, by 1819 a radicalized Cobbett had become one of his most vociferous defenders. To Cobbett, possession of Paine’s bones meant that he was the keeper of his legacy, the prophet of his relevance to the oppressed working classes of Georgian England and the United States.

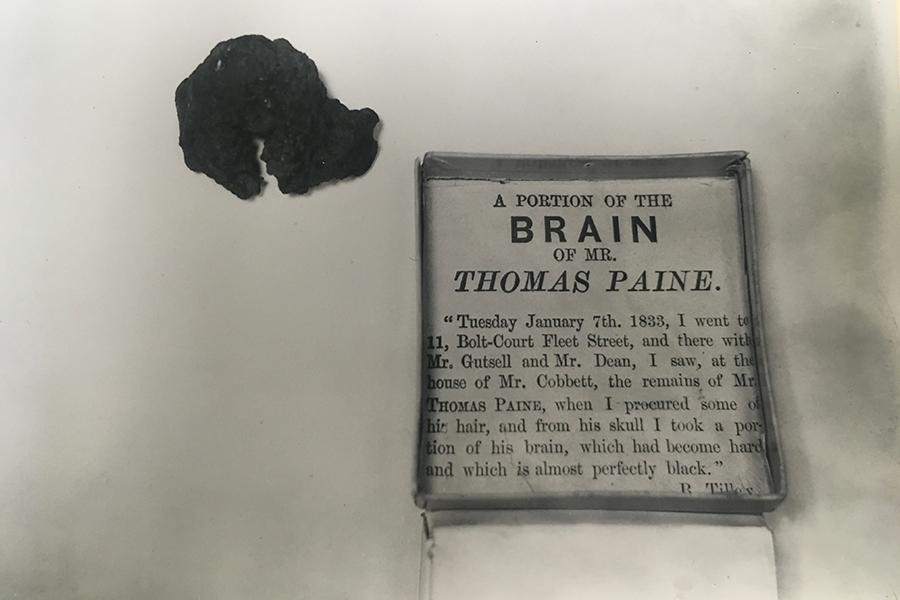

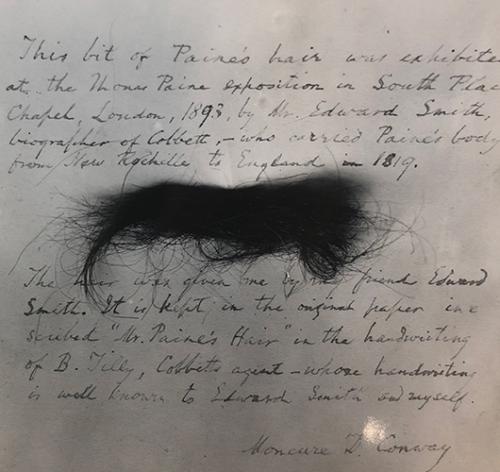

After Cobbett died in 1835, one of his sons supposedly etched his name on Paine’s skull, to ward off hucksters who claimed to possess the mortal remains of “Common Sense.” Apparently, corn merchant John Chennell purchased a box at auction after Cobbett’s death, not realizing it contained some of Paine’s bones; in 1849, Chennell off-handedly remarked to an interested stranger that the box sat quietly in his cellar. Charles Tilly, former assistant to Cobbett, maintained possession of Paine’s skull and brain. By the late 19th century, the contents of the box dispersed across England, prized possessions in the private collections of Paine admirers.2 In the 1880s Englishman George Reynolds, facing bankruptcy and needing cash, sold Paine’s brain and bones separately to several individuals and the British Museum.3

Paine’s skull and bones are still scattered out there somewhere: perhaps in an Australian widow’s possession, possibly in a private collection or silently resting in a museum archive, maybe buried somewhere near his birthplace in Lewes, England. As I think about what hidden corners of the world his remains might be at rest, I wonder what Paine would have thought about all the fuss over his remains, and the implied ownership of his intellectual and political legacy. Would the revolutionary with egalitarian instincts, the prophet of democratic politics, have wanted his mortal remains scattered across the globe in private collections?

- Sketches of the Life of Billy Cobb, and the Death of Tommy Pain, 2nd ed. (London: William Cobbett, 1820).

- Charles Tilly, “Notes and Queries,” (1869) MS, Thomas Paine National Historical Association Collection (TPNHAC), Institute for Thomas Paine Studies (ITPS) at Iona College.

- Moncure D. Conway to William Van der Weyde, 14 August 1906, Thomas Paine National Historical Association Collection, Institute for Thomas Paine Studies, Iona College.